The term “redface” refers to the misappropriation of Indigenous traditional dress, stereotyped speech patterns, and racialized face augmentation to act out an imaginary of Indigenous people. This is most often done by wearing feathers in one’s hair, red face paint, loin cloths or fringed deerskin, and full headdresses and war bonnets. Movements that mock traditional and ceremonial dances are also a type of redface.

The term “redface” refers to the misappropriation of Indigenous traditional dress, stereotyped speech patterns, and racialized face augmentation to act out an imaginary of Indigenous people. This is most often done by wearing feathers in one’s hair, red face paint, loin cloths or fringed deerskin, and full headdresses and war bonnets. Movements that mock traditional and ceremonial dances are also a type of redface.

In December 2022, the Great Plains Action Society posted a powerful article accompanied by testimonies of the Iowa City Community School District’s continued willful ignorance of important Indigenous issues. Testimonies from Indigenous students and parents outline several incidents in which teachers used outdated and harmful redface-oriented assignments and activities, ignored the resources Indigenous peoples have made for non-Indigenous people, and disregarded the Diversity & Cultural Responsiveness Committee recommendations.

Avoiding these issues creates inaccessible spaces for Indigenous children and contributes to the historic erasure of Indigenous peoples worldwide. Having young students play in redface and assigning curriculum that removes Native American history are part of a larger social and systemic injustice that institutions and individuals alike must address.

Redface and Protest

When I was in grade school in the mid 2000s, I learned that Boston Tea Party (1773) protesters wore redface to disguise themselves to avoid imprisonment or death. More recently, historians have argued that the Boston Tea Party redface was not simply to hide their identities but to distance themselves from European notions of citizenship and ally themselves with an imagined authenticity and claim to the land. Philip J. Deloria, Jr. writes in his classic Playing Indian, “In the years before the American Revolution (1765-1791), colonial crowds often acted out their political and economic discontent in Indian disguise. …Whether aimed at British officials or colonial landlords, misrule traditions, often performed in Indian dress, remained a vital mode of American political protest for more than a century.” (12)

Redface allowed colonists to become “native” Americans in the wake of the war for independence. Meanwhile, historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz explains in An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, settler-rangers waged a decade of “Indian wars” (1774-83) against “Indigenous noncombatants with the goals of total subjugation or expulsion.” (71) This newfound American identity that hinged on an Indigenous and European ancestry continued in American culture just as cultural and physical genocide of Indigenous people continued for subsequent centuries. Redface since the colonial era has taken many forms.

National Parks and Human Zoos

I, like many, can recall stepping into a park or campsite and seeing wood carvings of an Indigenous man in an eagle feather war bonnet, several faux totem poles, or a cabin punctuated with Navajo-style blankets and commercial dream catchers. These decoration choices are not innocent and highlight a longstanding stereotyped association of certain features of nature with Indigenous people.

In 1872, President Grant signed a bill designating 2.2 million acres of land to become public parks, and President Woodrow Wilson established the National Parks Service in 1916 to manage this land. In the process, many Indigenous nations were forcibly removed from their homeland to keep the parks “untouched.” At Yellowstone, for example, the Crow, Blackfeet, Bannock, Nez Perce, and Shoshone nations were barred from using the land until recently. As Mark David Spence remarks in Dispossessing the Wilderness : Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks, “Early park officials quickly realized that even the slightest fear of Indian attack could prevent tourists from experiencing all the benefits and enjoyments that Yellowstone had to offer the American people.” (85) Other national parks were modeled after Yellowstone. These coercive measures made by the National Parks coincided with many U.S. government efforts to aggressively assimilate Indigenous people through residential schools, religious practice suppression, and other forms of cultural genocide.

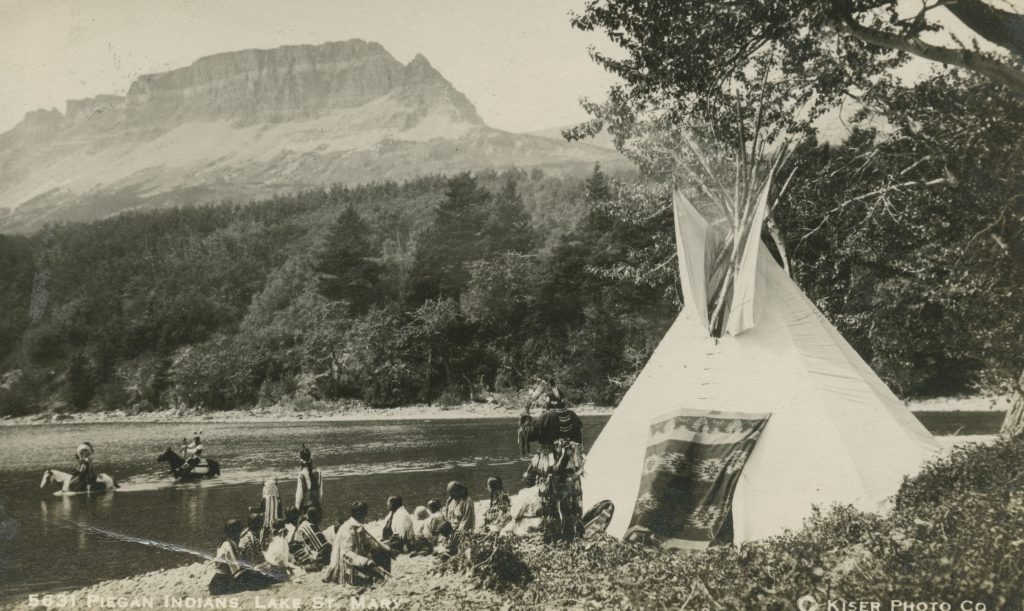

In other cases, Indigenous nations, like the Blackfeet Nation–who resided where Glacier National Park was established–were advertised as local novelties to be visited, posed with, and exhibited. According to Wyckoff, William, and Dilsaver’s “Promotional Imagery of Glacier National Park,” Indigenous peoples were featured in almost one-third of the promotional material for the park by the early twentieth century. The main hotel at the park was decorated with Blackfeet paintings, the main tourism entertainment was Blackfeet singers and dancers , and members of the nation often guided tourists on hunting and fishing outings. Meanwhile, the daily life of the Blackfeet Nation was portrayed at Glacier as park-affiliated attractions; many visitors felt confident taking pictures of or with the people they saw on their trek like they would the flora and fauna of the park.

Throughout the 20th century, Indigenous people, going about their day-to-day lives, were presented as relics of a lost history. At the time, many non-Native people believed that Indigenous people were destined for extinction, a myth often referred to as the “vanishing Indian.” Dunbar-Ortiz writes, “Commonly referred to as the most extreme demographic disaster– framed as natural–in human history, [the rapid, targeted decline in Indigenous peoples’ population] was rarely called genocide until the rise of Indigenous movements in the mid twentieth century forged questions.”(79) With this “vanishing Indian” myth in mind, parks often advertised the Indigenous nations as being a limited-time-only attraction and positioned themselves as mediators between the past and present. Park guests were often encouraged to dress up as the Indigenous people around them and take pictures of and with them, like they might a costumed character at a Disney theme park. Parks assumed the aesthetic aspects of the Indigenous cultures who lived there to create immersive experiences for guests. Both the parks and park visitors posited themselves as Indigenous in ways that still kept Indigenous people at arm’s length. Indigenous people were characters in a fantasy world for tourists to enjoy and parks to exploit.

Scouts and Children Playing Indian

While Indigenous children were being kidnapped and transported to residential boarding schools between 1819 and 1969–abused and tortured for speaking their languages–white children were taught loose renditions of Native traditions and encouraged to dress up in warbonnets, a type of headdress that is only given to leaders of Indigenous nations to wear for special occasions and sacred to many Great Plains nations. At the turn of the twentieth century, Ernest Thompson Seton developed a youth development program called the “Woodcraft Indians”; to him, the Boy Scouts of America had become too militaristic and diverted boys from nature. Seton believed that through redface dress and activities, troubled boys could become more American and learn skills like wood crafting and agriculture. He created a mock tribe called the “Sinaways” and had the boys make “Indian costumes.”

While Indigenous children were being kidnapped and transported to residential boarding schools between 1819 and 1969–abused and tortured for speaking their languages–white children were taught loose renditions of Native traditions and encouraged to dress up in warbonnets, a type of headdress that is only given to leaders of Indigenous nations to wear for special occasions and sacred to many Great Plains nations. At the turn of the twentieth century, Ernest Thompson Seton developed a youth development program called the “Woodcraft Indians”; to him, the Boy Scouts of America had become too militaristic and diverted boys from nature. Seton believed that through redface dress and activities, troubled boys could become more American and learn skills like wood crafting and agriculture. He created a mock tribe called the “Sinaways” and had the boys make “Indian costumes.”

In 1905, Dan Beard created the “Sons of Daniel Boone,” which taught young boys to be “good Americans” by emanating white historical actors. This form of patriotism lionized pioneers and early Americans and oftentimes imagined the Sinaways as their natural enemies. In both cases, play and dress informed the teaching of these young boys and instilled the idea that a good American was white and non-Native.

Ultimately, Seton’s Woodcraft Indians model of youth development became extremely popular, which likely resonated with the cultural antimodernism and “ret urn to nature” sentiments reflected in the 19th- and early-20th-century investment in National Parks. Meanwhile, the Boy Scouts adopted Beard’s historical reenactment model, which aligned with their patriotic ideals.

urn to nature” sentiments reflected in the 19th- and early-20th-century investment in National Parks. Meanwhile, the Boy Scouts adopted Beard’s historical reenactment model, which aligned with their patriotic ideals.

Games like “Cowboys and Indians” were an encouraged way of play for non-Indigenous children throughout the 20th century. Playing in redface was popular for school plays and Thanksgiving celebrations, throughout Iowa and across the U.S. As noted in the Great Plains Action Society testimonies, it is hardly a thing of the past. Encouraging white children to romanticize a “vanished” demographic or idolize patriots of the past made redface an ingrained and sanctioned cultural practice for generations to come. Meanwhile, the U.S. government continued to force Indigenous nations to assimilate and abandon their many cultures. Practices, however loose, and dress of Indigenous peoples were now a privilege afforded to white Americans.

Today

All of the redface photos used in this blog–photos of and by non-Indigenous people–come from the Fortepan Iowa collaborative portal, which preserves everyday Iowa family snapshots. These photos display several historic assumptions about Indigenous peoples that still linger today and reiterate the historic traumas of colonization, stereotyping, and erasure. Fortepan Iowa has chosen to display them to remind Iowans of this history and has worked with the Great Plains Action Society to create disclaimers for these photos and photos of other racially sensitive images.

The Fortepan Iowa collaborative portal, our disclaimers, and this blog post aim to show a true Iowa and U.S. history , and help Iowans contextualize this history. Redface practices–in school plays, as Halloween costumes, in film, and as mascots– still exist today. This practice is not part of our proud history, but rather a reminder of all the work that needs to be done by non-Indigenous people.